Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775‑1851)

Sun Setting over a Lake

Date Painted: c.1840

Medium: Oil paint on canvas

Dimensions: 1074 x 1377 x 145 mm

Collection: Tate Gallery, London

Turner's Heaven or Hell?

Here is what I wrote on Sun Setting Over a Lake:

Turner’s gentle pastel colored canvasses do not shy away from these contrasts. In "Sun Setting over Lake", the blue of the sky (intermingled with the white and pale mauve clouds) provides a close to perfect diagonal mirror image to its opposite orangish-yellows. The center of each, with the tiny dot of a sun and its halo on one side and the small swirl of clouds on the other, equidistant from each other, once again suggesting a relationship of opposites. The pale blue seems to be softly pulling us farther and deeper into some unknown realm, whereas the bright firey yellows are inviting us to plunge in. Could it be a commentary on Heaven and Hell?

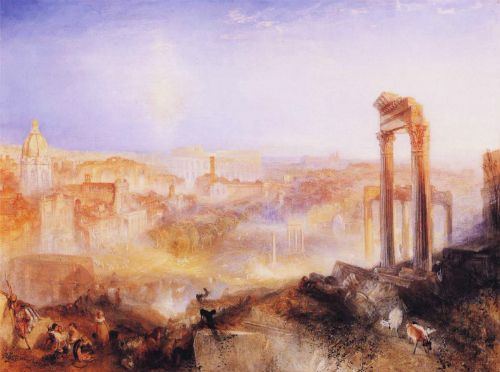

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775‑1851)

Modern Rome - Campo Vaccino

Date Painted: 1840

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 36 1/8 x 48 1/4 in.

Collection: J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

And below is what I wrote in my Camera Lucida blog about Modern Rome:

Many of Turner's contemporaries believed his art came from the devil, except for his devout follower, the art critic John Ruskin. Here is an article I wrote on Turner which I titled: Turner's Contrasts.

I think Turner was the precursor to the Impressionists, who led the way to abstraction, which, I think, is the end of art. Perhaps his fellow critics were right, after all. Still, I cannot but be mesmerized by his works.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775‑1851)

Modern Rome - Campo Vaccino

Color Beginning

Date Painted: 1819

Medium: Watercolor

Dimensions: 22.5 x 28.6 cm

Collection: Tate Gallery, London

I have a rough paper photocopy of this painting above (which I got from an art book), which I framed and had hanging up for a long time. The wispy, watery atmosphere of the painting, where the golden sand mingles with the dusky horizon, all of which blend into sea, air, then sky, is perhaps Turner's attempt at creating heaven, or the passage to heaven. He was a youngish man then, forty-four years old. Too young to contemplate this paradisaical scene. His later works turned darker, more pessimistic, and ultimately more nihilistic.

Here is what Kenneth Clark says in his book Civilization about Turner's mingling of sea, air and sky:

[Turner] was particularly fascinated by the line where the sky and the sea join each other, that mingling of elements which seems, by its harmony of tone, to lead to a general reconciliation of opposites. (Clark, p. 199)Below is his Sunrise with Sea Monsters. An ephemeral vision, with horrors lurking in the backtround. It was painted in 1845, six years before his death at age seventy-six.

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775‑1851)

Sunrise with Sea Monsters

Date Painted: c. 1845

Medium: Oil on canvas

Dimensions: 91.5 x 122 cm

Collection: Tate Gallery, London

Finally, The Angel Standing in the Sun:

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775‑1851)

The Angel Standing in the Sun

Date exhibited: 1846

Medium: Oil paint on canvas

Dimensions: 942 x 942 mm

Collection: Tate Gallery, London

Here is what the Tate Gallery writes on Angel Standing in the Sun:

This late painting shows the Archangel Michael appearing on the Day of Judgement with his flaming sword. In the foreground are Old Testament scenes of murder and betrayal: Adam and Eve weeps over the body of Abel (left), and Judith stands over the headless body of Holofernes (right).The Web Gallery of Art suggests that the Angel is:

Turner's pessimistic picture seems to show death is everywhere in this fallen world.

It may also reflect his concern that his own life and art would be judged. He got his revenge on his critics by showing the painting with lines describing 'the feast of vultures when the day is done.'

...none other than the Angel of the Apocalypse from the biblical Book of Revelation.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A reader sent me an email with a suggestion on the "Nature" topic:

[L]et me think about ideas I could write for the defense of beauty. They would be centered on natural history, especially flowers and plants.I'm currently reading Kenneth Clark's Civilization. I started looking through the book (I've read it at least once before) since he boldly calls his book "Civilization," not Western, or European or Modern Civilization. No, no qualifier. Just "Civilization." And he clearly means Western civilization, which he starts from the Greco-Roman period. No Chinese civilization, no Persian civilization, no African civilization. But he does have a few lines about Islam:

The materialists and atheists have no rational basis for defending beauty (and it shows!) and this forms one of the most interesting themes to discuss ideas I think. It seems incredible that we should have to defend beauty as it is one of the pillars of social development. It reflects poorly on traditionalists that liberals predominate in nature conservation philosophy and action.

....in the middle of the seventh century there appeared a new force, with faith, energy, a will to conquer and an alternative culture,: Islam. The strength of Islam was its simplicity...Mohamet, the prophet of Islam, preached the simplest doctrine that has ever gained acceptance; and it gave to his followers the invincible solidarity that once directed the Roman legions. (Clark, p. 7)So he views Islam as an alternate, alien force, but he describes its simplicity as its strength, unlike all the other Western evolution of civilization, to the extent that they become too complicated like the late Baroque period of the 18th century. The only Western period we may discuss in terms of relative simplicity is the Post-modern period, but even its artists and philosophers believe that they are adding on to what the past has given them, not just chiseling it down to elemental forms.

In its most defining sense, "civilization" is a Western concept. Here is what Clark says about the word, when he was asked to a series on civilization:

The BBC wanted a series of colour films on art, and thought that I might be able to advise them. But when David Attenborough, then responsible for BBC 2, asked me to do so, he used the word Civilisation, and it was this word alone that persuaded me to undertake the work. I had no clear idea what it meant, but I thought it was preferable to barbarism, and fancied that this was the moment to say so. In a very few minutes, while the lunch of persuasion went cheerfully on around me, I had thought of a way in which the subject could be treated, and from that first plan I departed very little. It was concerned only with Western Europe. Obviously, I could not include the ancient civilisations of Egypt, Syria, Greece and Rome, because to have done so would have meant another ten programmes, at least; and the same was true of China, Persia, India and the world of Islam. Heaven knows, I had taken on enough. Moreover, I have the feeling that one should not try to assess a culture without knowing its language; so much of its character is connected with its actual use of words; and unfortunately I do not know any oriental languages. Should I then have dropped the title Civilisation? I didn't want to, because the word had triggered me off, and remained a kind of stimulus; and I didn't suppose that anyone would be so obtuse as to think that I had forgotten about the great civilisations of the pre-Christian era and the East. However, I confess that the title has worried me. It would have been easy in the eighteenth century: Speculations on the Nature of Civilisation as illustrated by the Changing Phases of Civilised Life in Western Europe from the Dark Ages to the Present Day. Unfortunately, this is no longer practicable. (Clark, p. xvii])I skipped around the book, looking at the chapter headings, or the index at the back, to chose a topic. There is a full chapter titled: "The Worship of Nature." After the reader's comment, I decided to skim through the chapter. And here is an intriguing and perceptive commentary on Turner, about whom I have posted a full article here.

Here are the excerpts from Civilization on Turner:

[W]hen an ordinary traveller of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries crossed the Alps it never occurred to him to admire the scenery - until the year 1739, when the poet Thomas Gray, visiting the Grande Chartreuse, wrote in a letter: 'Not a precipice, not a torrent, not a cliff, but is pregnant with religion and poetry.' Amazing! Might have been Ruskin. In fact I don't think that the full force of alpine poetry was expressed till the time of Byron and Turner. But in the middle of the eighteenth century a good many people seem to have recognised the charm of the Swiss lakes and enjoyed them in a comfortable, dilettantish sort of way. There even arose a Swiss tourist industry that supplied travellers in search of the picturesque with mementoes and produced one remarkable, almost forgotten artist, Caspar Wolf, who anticipated Turner by almost thirty years. But like the eighteenth-century English nature poets, this is a provincial overture, which might never have become a part of contemporary thought without the genius of Rousseau (Clark, pp. 278-279).I have written an article on Turner. I was enchanted by him ever since I discovered him going through art books in my University's library. It was almost like a spell for a while. I have even painted my own Turneresque piece:

[...]

In the same years that English poetry took its revolutionary course English painting also produced two men of genius, Turner and Constable (Clark, p. 280).

[...]

Turner was the supreme exponent of that response to nature felt by Gray in the Grande Chartreuse - what one might call the picturesque sublime; and sometimes his storms and avalanches seem preposterous, just as Byron's rhetoric is preposterous. But I suppose that the new religion required assertions of power and sublimity more obvious than those provided by daisies and celandines.

Don't think that I am trying to belittle Turner. He was a genius of the first order - far the greatest painter that England has ever produced; and although he was prepared to work in the fashionable style, he never lost his intuitive understanding of nature. No one has ever known more about natural appearances, and he was able to fit into his encyclopedic knowledge memories of the most fleeting effects of light - sunrises, passing storms, dissolving mists, none of which had ever been set on canvas before.

For thirty years these brilliant gifts were exploited in a series of pictures which dazzled his contemporaries, but are too artificial for modern taste. But all the time Turner was perfecting, for his own private satisfaction, an entirely new approach to painting which was only recognised in our own day. Briefly, it consisted of transforming everything into pure colour, light rendered as colour, feelings about life rendered as colour. It's quite difficult for us to realise what a revolutionary procedure this was. One must remember that for centuries objects were thought to be real because they were solid. You proved their reality by touching or tapping them -people still do. And all respectable art aimed at defining this solidity, either by modelling or by a firm outline. 'What is it,' said Blake, 'that distinguishes honesty from knavery, but the hard and wiry line of rectitude?'

Colour was considered immoral - perhaps rightly, because it is an immediate sensation and makes its effect independently of those ordered memories which are the basis of morality. However, Turner's colour was not at all arbitrary - what we call decorative colour. It always started as the record of an actual experience. Turner, like Rousseau, used his optical sensations to discover the truth. 'I feel therefore I am.' It's a fact which you can verify by looking at Turner's pictures in the Tate Gallery: the less defined, the more purely colouristic they are, the more vividly do they convey a total sense of truth to nature. Turner declared the independence of colour and thereby added a new faculty to the human mind.

I don't suppose that Turner was conscious of his relationship with Rousseau. But the other great prophet of nature, Goethe, meant a lot to him. Although he had practically no education, he painfully read Goethe's works, in particular his Theory of Colour, and he sympathised with Goethe's feeling for nature as an organism, as something that works according to certain laws. This, of course, was one of the things about Turner that delighted Ruskin, so that his enormous defence of the artist, which he called by the wholly misleading title of Modern Painters, became an encyclopedia of natural observation. Just as the Middle Ages produced encyclopedias in which inaccurate observations were used to prove the truth of the Christian religion, so Ruskin accumulated very accurate observations of plants, rocks, clouds, mountains, in order to prove that nature worked according to law [198]. Well, perhaps it does. But not the kind of law that human beings have concocted for themselves. Nobody today would take seriously Ruskin's belief that nature is subject to, or illustrates, Moral Law. All the same, when he says, 'The power which causes the several portions of a plant to help each other we call life. Intensity of life is also intensity of helpfulness. The ceasing of this help is what we call corruption,' he does seem to me to have drawn from his observations a moral at least as convincing as most of those that can be drawn from Holy Writ. And it helps to explain why, for fifty years after the publication of Modern Painters, Ruskin was considered one of the chief prophets of his time (Clark, pp. 284-285).

Turneresque

Kidist P. Asrat

Painted ca. 2009

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------