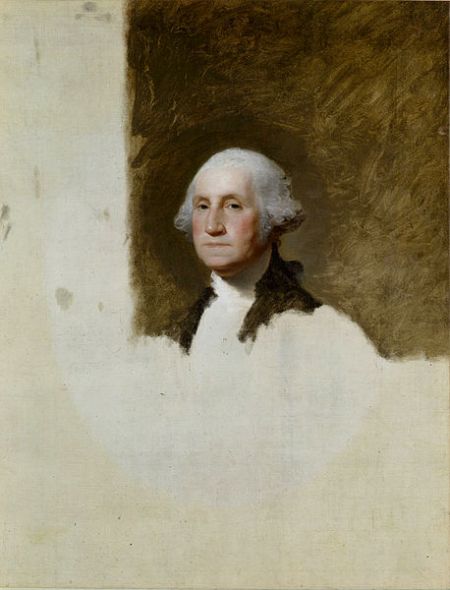

Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828)

George Washington: The Athenaeum Portrait

1796

Oil on canvas

48 x 37 in

Jointly owned by the National

Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian

Institution, Washington

and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The article below is a compilation of several posts from my blogs Camera Lucida and Our Changing Landscape:

- Forces of Nature

- Washington: The Legend

- The State of Affairs of Our Modern world.

I will put it in one of the following Reclaiming Beauty chapters: Beauty Truth and Goodness, Beauty in Art, or Beauty in Culture and Society under Myths and Legends, with the same title: The Truth That Follows George Washington.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

George Washington's prolific portraitist, Gilbert Stuart, painted approximately seventy-five portraits of the President, but used three portraits as references for all the rest (1). The Athenaeum Portrait is Stuart's most reproduced portrait, and is so called after the Boston Athenaeum which originally bought it. Stuart never finished this portrait. It was Washington's second sitting with Stuart, and perhaps Stuart didn't yet know how to appease the irritable Washington, who might have thought portrait painting a frivolous affair, and didn't like the long sittings. By the time Stuart painted his third portrait, he know that he could appease the accomplished equestrian through discussions about horses. The other two portraits are the Vaughan Portrait, where Washington is facing to his left, and the Landsdowne Portrait of Washington in full-length. The portraits are named after the owners. In the Athenaeum, Washington is facing to his right.

The Athenaeum Portrait provides an extraordinary vision of the President. Despite its unfinished state, Stuart manages to convey a strong vision of Washington emerging as though from some primordial matter, like a force entering our world. It was as though Washington were completely formed, somewhere behind the canvass, and Stuart was simply pulling him out with his brush and paint tools.

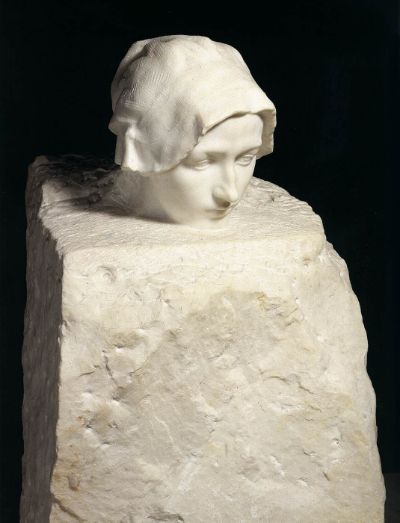

The French sculptor Rodin said that he could see the forms within the stones he chose for his sculptures, and all he he did was to entice them out of their hiding. He also left unfinished works, perhaps finding these forces to strong, and too alive, to contend with (2).

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917)

Thought

1886-89

Marble

Height 74 cm

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

In 1886 Rodin began modeling a portrait of Camille Claudel in traditional costume. When his assistant Victor Peter, executing the work in marble, reached the collar, Rodin made him stop: the head emerging from the block offered the contrast, as in Michelangelo, of a finished section imprisoned in the rough-hewn stone. This triumph of sculpture was exhibited as it was at the Salon in 1895, entitled Head. Only later did it receive its Symbolist title of Thought Emerging from Matter, then simply Thought (3).Perhaps Stuart, like Rodin, was aiming for something bigger than he could handle. But, it is a calm Washington that emerges in the Athenaeum Portrait, exuding a steady temperament and ready to enter our world and to put it right. It is the unfinished nature of the painting which conveys this, and Stuart may be a greater artist than I give him credit for. This portrait is probably as much about Stuart's perseverance and patience as it is about Washington's character.

The Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. explains Stuart's technique for the Athenaeum Portrait (4):

The strikingly fresh aspect of this life portrait of Washington comes from Stuart's application of subtly varied skin tones in separate, unblended touches of the brush. His technique is visible even in the shaded areas under the chin, where Stuart alternated darker and lighter flesh tones to indicate shadow and reflected light. The president's white-powdered hair and blue eyes stand out in contrast.And the biographical notes on Stuart at the National Gallery of Art biography say this (5):

[Stuart] used it [the Athenaeum Portrait] throughout his career to make approximately seventy-five replicas, and the image - carefully built up with contrasting flesh tones - is one of Stuart’s most accomplished portraits.Stuart spent time on Washington's face, once again supporting my idea that the process exhausted his artistic energy. He used this completed (or detailed) visage as his reference for his many other completed paintings of Washington, since perhaps using a painting reproduction was an easier reference than Washington himself.

Pictures don't lie, at least I don't think they do. And they often succinctly tell us truths which can easily be camouflaged by clever words or clever techniques. Despite Stuart's difficulties, he gave us one of the best portraits of Washington, depicting both his strength and his wisdom.

Another artist, the French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon, produced a life-like bust of Washington, which is now at the Morgan Library in New York (6). Houdon made a cast of Washington's face, and returned to France to complete his work. Washington had to remain behind the drying mask with his eyes closed, and Houdon had to use his creative powers to bring to bring life back into Washington's eyes. Like his countryman Rodin, he let the sculpture breath its own life in to the bust, and like Stuart, he gave Washington the calm, confident strength. As described in Ron Chernow's Washington: A Life (7):

The conscientious Houdon...asked if he could shadow Washington on his daily rounds and study his face and movements in social interactions. During the next two weeks he even attended a funeral with Washington and took part in the wedding of George Augustine Washington and Fanny Bassett. It reveals a good deal about Houdon’s genius that the most expressive moment for him came when Washington flared up indignantly as he haggled over a pair of horses; always a tough bargainer, Washington thought the other trader was asking too much. During this sudden flash of anger, Houdon thought he spied the inner steel in Washington’s nature.Chernow continues with Houdin's paring down the bust to "essential truths about Washington":

Methodical in his own habits, Washington was naturally fascinated by the systematic effort that Houdon poured into each step of the artistic process. On October 6 the Frenchman began working on a terra-cotta bust that was likely a preliminary step in creating the full-length sculpture.Lawrence Auster wrote about Washington in a similar fashion (8):

...To the extent possible, Houdon dispensed with artistic conventions and pared down the bust to essential truths about Washington, making him life-size and lifelike. The sculpted face is strong and commanding, and the skin smooth, without the crags time later carved into the cheeks. As Washington turns his head, his shrewdly appraising eyes seem to scan the far horizon. Washington’s expression is forceful, his determination evident in his narrow gaze, matched by the muscular strength of his shoulders. Because his hair isn’t fluffed out at the sides, the bust accentuates the hard, lean strength of his face. Houdon captured both the aggressive and the cautious sides of Washington, held in perfect equipoise.

We are so accustomed to the Gilbert Stuart portraits, painted in Washington’s sixties when he was already showing premature signs of age (though his firmness of character was not diminished), that it can be a shock to see a more vital Washington. Here is a marvelously life-like image of the then 53-year-old Washington rarely seen by Americans, one of the heads sculpted by Jean Antoine Houdon from the life mask he cast when he visited Mount Vernon in 1785, now at the Museum of the Louvre in Paris. Houdon told a friend he was in awe of "the majesty and grandeur of Washington’s form and features." One has the same awe at Houdon’s genius; it is to be doubted that any photograph could make us feel that we are as close to the living man as he really was.

High Park Cherry Tree

Photograph by: Kidist P. Asrat

ca. 1997

And Truth was never far behind Washington. A famous legend which followed him throughout his life recounts his awakening to truth when confronted by his father (9):

Never did the wise Ulysses take more pains with his beloved Telemachus, than did Mr. Washington with George, to inspire him with an early love of truth. "Truth, George"' (said he) "is the loveliest quality of youth. I would ride fifty miles, my son, to see the little boy whose heart is so honest, and his lips so pure, that we may depend on every word he says. O how lovely does such a child appear in the eyes of every body! His parents doat on him; his relations glory in him; they are constantly praising him to their children, whom they beg to imitate him. They are often sending for him, to visit them; and receive him, when he comes, with as much joy as if he were a little angel, come to set pretty examples to their children."But George Washington had told a lie, when he was six years old (10):

When George," said [an excellent lady], "was about six years old, he was made the wealthy master of a hatchet! of which, like most little boys, he was immoderately fond, and was constantly going about chopping every thing that came in his way. One day, in the garden, where he often amused himself hacking his mother's pea-sticks, he unluckily tried the edge of his hatchet on the body of a beautiful young English cherry-tree, which he barked so terribly, that I don't believe the tree ever got the better of it. The next morning the old gentleman [Washington's father] finding out what had befallen his tree, which, by the by, was a great favourite, came into the house, and with much warmth asked for the mischievous author, declaring at the same time, that he would not have taken five guineas for his tree. Nobody could tell him any thing about it. Presently George and his hatchet made their appearance. George, said his father, do you know who killed that beautiful little cherry-tree yonder in the garden? This was a tough question; and George staggered under it for a moment; but quickly recovered himself: and looking at his father, with the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth, he bravely cried out, "I can't tell a lie, Pa; you know I can't tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet."--Run to my arms, you dearest boy, cried his father in transports, run to my arms; glad am I, George, that you killed my tree; for you have paid me for it a thousand fold. Such an act of heroism in my son, is more worth than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver, and their fruits of purest gold.The story is of course not only of telling the truth, but of telling the truth after one had told a lie. To recant, to accept one's guilt, and to rectify the error is what George Washington did, and why his father so whole-heartedly forgave him. And why we still hold this legend dear, which gives us the essential truth about George Washington.

It is a great legend to have for a nation's founding leader.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

1. Gilbert Stuart: Philadelphia (1794-1803). Notes on the National Gallery Art Exhibition, March 27-July 31, 2005.

http://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2005/stuart/philadelphia.shtm

2. Thought (Portrait of Camille Claudel). Web Gallery of Art

http://www.wga.hu/html_m/r/rodin/3busts/claudel.html

3. Ibid

4. Gilbert Stuart. George Washington: The Athenaeum portrait. The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C.

http://www.npg.si.edu/cexh/stuart/athen1.htm

5. Gilbert Stuart: Philadelphia (1794-1803). Notes on the National Gallery Art Exhibition, March 27-July 31, 2005.

http://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/2005/stuart/philadelphia.shtm

6. Gilbert Stuart George Washington Life Mask: Morgan Library, New York.

http://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/gwlifemask.asp

7. Chernow, Ron (2010). Washington: A Life. p. 511. Penguin USA.

8. Auster, Lawrence. (February 20, 2004). Washington's Birthday. View From the Right.

http://www.amnation.com/vfr/archives/002212.html

9. Mason Locke Weems (1809). The Fable of George Washington and the Cherry Tree

In: The Life of Washington. M.E. Sharpe. 1996 Armonk NY

10. Ibid

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Posted By: Kidist P. Asrat